By David Knibb in San Antonio Photography by Simon Buckley

Liberated from a decade of government ownership, Mexicana now faces both the opportunities and the perils of freedom

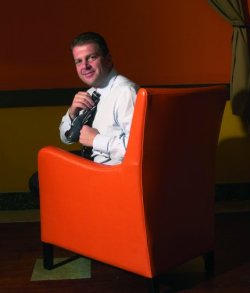

Managing director Emilio Romano recalls the day last November when Mexicana was sold. “I was in my office when the announcement came in that the Cintra board was recommending the sale of Mexicana. There was a lot of loud shouting and screaming. We were able to share our emotions after so many years of hard dreams. Finally, we knew we would have our own future.”

That day must have seemed a long time coming. For 10 years the once-proud airline had languished as a wholly owned subsidiary of Cintra, a holding company controlled by Mexico’s government. With that status, Mexicana was under common ownership with its arch-rival Aeromexico. It was without access to capital, and subject to oversight by owners that were not interested in running airlines. For Mexicana it must have been like a prison sentence.

Grupo Posadas, a privately held Mexican hotel chain, was Mexicana’s liberator. The group paid $166 million in cash, assumed bank and trade liabilities of $294 million, and assumed fleet obligations (mostly leases) of $997 million. With this $1.5 billion commitment, it acquired all of the Mexicana group, which includes its low-cost carrier Click. Grupo Posadas not only bought the government’s two-third stake in Mexicana, but also the other third that was held by banks or public shareholders. Speaking to Airline Business in March at the Network route planning event in San Antonio, Texas, Romano explained: “Once the sale was approved, Mexicana ceased to be publicly traded as part of Cintra.”

Both Mexicana and Aeromexico lost their independence in 1995 during La Crisis, the peso devaluation that nearly bankrupted Mexico. Banks took over both airlines, capitalised their debts, and created Cintra as a holding company for them. The competition commission CFC blessed the deal so long as Mexicana and Aeromexico kept separate identities and management. Cintra was supposed to be a stopgap measure.

Within two years Mexico recovered, partly by bailing out its banks. Most of them sold their Cintra stakes to the government, which then became the majority owner. Meanwhile, complaints about collusion between Aeromexico and Mexicana prompted a CFC inquiry and its conclusion that the airlines should be separated again.

| Mexicana at a glance Revenue $1.52 billion |  |

Debate raged for the next few years over that conclusion. Opponents, including the secretary of transportation, argued that breaking up Cintra would weaken both airlines and send them into new tailspins. In the end the CFC prevailed, but on condition that Cintra could wait until the market was better for selling airlines.

When Romano took over in 2004, the arguments over Mexicana’s future had subsided, but the patient was in trouble. Cintra had just reported a consolidated $189 million loss for both airlines. By all accounts, Aeromexico was the worst off. That prompted Cintra to move the veteran Fernando Flores from managing director of Mexicana to Aeromexico in an effort to fix the damage. One can only imagine what Flores found, but when Romano replaced Flores at Mexicana he recalls: “We had almost $380 million in interest-bearing debt, and only $40 million in cash.”

“We were not subsidised at all,” Romano explains. “Actually, we were asked to be on time in paying for jet fuel and airport fees because we were quasi- governmental. So we were in the worst possible situation as we had little money, but were supposed to be the poster child.” The airline had no money to even buy coffee, Romano recalls, “so the flight attendants used to bring coffee from their homes to serve the passengers.”

Amid such hard times, the debate over Mexicana and Aeromexico resumed. Cintra begged the CFC for permission to merge the two ailing airlines. Finally, with a host of conditions, the CFC relented. But then Cintra changed leaders. Late in 2004 Andres Conesa took over and he soon jettisoned the merger idea. In its place, Conesa launched a detailed plan to sell the two carriers separately. A year later, the product of that plan was Grupo Posadas’s purchase of Mexicana.

How could anyone run an airline under such conditions? Romano tried, but Mexicana’s owners clearly were focused on other things. “The government wasn’t interested in a business plan or a long-term fleet plan,” Romano recalls. “Their mandate was short term – to sell the assets and recover their losses from the earlier crisis. They had no interest in long-term plans.” Against this background it is not hard to see what all the cheering was about last November.

Financial restructuring Even before the sale, Romano was doing what he could to energise Mexicana. He launched a fleet modernisation plan, started to restructure finances, and converted subsidiary Aerocaribe into Mexico’s first low-cost carrier: Click. Cintra encouraged these moves; it hoped they might enhance the sale price. But the government was in no position to help.

Even before the sale, Romano was doing what he could to energise Mexicana. He launched a fleet modernisation plan, started to restructure finances, and converted subsidiary Aerocaribe into Mexico’s first low-cost carrier: Click. Cintra encouraged these moves; it hoped they might enhance the sale price. But the government was in no position to help.

So far, Grupo Posadas has not whipped out its chequebook either; nor has Romano asked for it. The new owners have that capability, but for now he is content simply to know that he enjoys the confidence of a well-capitalised, 39-year old company that is run by savvy businessmen. “They have invested their money and their faith in us,” he says. “We feel the weight of that responsibility. If before we were committed 100% to the future of Mexicana, with their vote of confidence our commitment is now 200%.”

He likes the new working relationship. “Our new corporate structure is more effective. Approvals are quicker whenever we need to move fast. When the government was in control the paperwork took a long time. This structure also provides a sounding board so we can share our views.”

For the first time Romano can remember, Mexicana has owners who actually are interested in its strategy. But he does not see them as micro-managers. “Grupo Posadas president, Gaston Azcarraga, chairman of our board, says he wants to validate our business plan but not interfere in our management. They believe we are the ones to carry out the plans.” Romano follows the view of US cowboy-philosopher Will Rogers, who quipped: “Even if you’re on the right track, you’ll get run over if you just sit there.”

Mexicana does several things well, but Romano is determined that it should do them better. It is the largest international carrier out of Mexico by far, and earns 60% of its revenue from that. It serves Central America, three South American cities, three in Canada, and 16 in the USA. “We are shifting more of our capacity to international,” he explains. “Our dollar-based revenue grew almost 15% over the last 12 months with a 4% increase in capacity.”

“International growth will be even more aggressive,” Romano predicts, “especially in the USA. We are the largest Hispanic carrier in that market, and we plan to grow.” In rapid-fire succession, he lists the next six US cities where Mexicana plans to go: Bakersfield and Fresno in California; Dallas and San Antonio in Texas; New Orleans and Las Vegas.

“We are mostly looking at high-growth Hispanic areas,” he explains. With Hispanics projected to become America’s second largest minority, that translates into many more flights. Mexicana’s fleet of 60 jets, mostly of the Airbus A320 family, fits these stage lengths, but Romano is also eyeing the long haul. He never mentions Europe, but “five years from now I would see Mexicana flying to Asia – not only China – but other markets in Asia.”

Mexicana’s other plan for staying on the right track is with high-yield traffic. Excluding Click, it flies only a quarter of Mexico’s domestic capacity, but still earns 40% of its revenue from this market. Romano wants Mexicana to be the carrier of choice for business travellers. To ensure this, flights at Mexico City are timed to facilitate connections. And improvements are under way – a new first class, new chef, new wine director, better on-time performance (already Mexico’s best), and new in-flight entertainment. Romano stresses: “Our missions are to serve the trans-border Hispanic traveller and the high-yield business traveller.”

Freedom, of course, comes at a price. Mexicana not only is free to pursue its goals, but it must also face the real-world market that it finds. It is a market that is radically changing. Cintra’s part-privatisation has helped stimulate an unprecedented liberalisation in Mexico’s skies. “Mexico is evolving from a protected environment,” Romano observes, “to one that is highly competitive. We are seeing the most intense and concentrated launch of low-cost carriers in the history of aviation. The entry of these new airlines, most of them well-funded, and the conclusion of Cintra with new owners will see Mexican aviation develop as much in the next two to three years as it did in the past 10.”

Most legacy carriers would tremble at the approaching war. And Romano predicts that local airlines with older aircraft, such as Aviacsa and AeroCalifornia, will be “very challenged”. But Mexicana sees itself as above the fray. “We are not going to cut service or lower prices to compete with the low-cost carriers,” Romano says. “Click will compete with them. That’s what it is for. Mexicana will continue to compete on the basis of its service.”

Romano’s bigger concern is the US market, where liberalisation of a different sort poses a threat. The recently revised bilateral allows another carrier from each country on any city pair. With US airlines already claiming over half the trans-border traffic, they are swarming onto new routes like locusts. At the last count, Washington has awarded at least 30 new Mexican routes to US combination carriers and nine to all-cargo airlines. Ironically, Romano notes, US rivals are drawn to Mexico to escape the low-yield environment at home caused by the likes of Southwest and JetBlue.

Facing these new competitors is only part of Mexicana’s problem. “The USA is a sophisticated market,” Romano notes. “Government support after 9/11 and the ability of US airlines to operate in Chapter 11, which Mexican airlines cannot do, equates to a subsidy. It is very difficult to compete with that when you’re in a country with low capital.”

Romano can take some comfort from the preference of Hispanic passengers for his airline over the US carriers. But it already claims only 26% of all Mexico-US traffic. Mexicana has to worry that as the US carriers start to compete with each other on Mexican routes, they will start to compete for the Mexicans too.

The answer, according to Romano, is to keep Mexicana’s costs low. They are already 40% below US rivals, he claims. And even though he will leave the head-to-head combat with Mexico’s new low-cost carriers to Click, he knows he cannot let the gap between their domestic fares and Mexicana’s grow too wide.

Romano has been on a cost-cutting crusade at Mexicana since he arrived. Early on he pressed for more commonality, the A320 family, and a younger fleet, which now averages 6.3 years. In his first year he convinced Mexicana’s staff to take a 10% pay cut.

Improved efficiency and those first cuts saved 7% a year, Romano claims. Now his sights are set on saving another 20%. He cut staff 5% last year; another 5% are set to go. The airline has “renegotiated everything from insurance to airport landing fees”, including its contract with distribution system Sabre. Aircraft and engine leases are the next targets.

Romano has focused on boosting aircraft utilisation – up from 10 to 12.5 hours a day. He accomplished this by shortening turnaround times to a 25- minute average, adding another maintenance shift to reduce aircraft downtime for heavy checks, and flying more “red-eyes”, especially on Mexico-US routes. Trans-border passengers seem to prefer them. His goal is to push utilisation up close to 13 hours. This, he predicts, will create “three more virtual aircraft”.

Maximum profit

“The last item in this cost-cutting strategy,” he says, “is to monitor our profitability for each flight and route to make sure we are maximising our network.” This exercise recently led the carrier to withdraw from Ecuador, where traffic met expectations but yields did not. Domestically, he adds, “we have transferred some routes to Click, but last year we closed stations in Durango, Hermosillo and Manzanillo because we were not able to make a profit.”

|

Already Mexicana and Grupo Posadas are pondering a public offering. “An IPO is one of many options we are now looking into as a way to increase our capital structure and to structure the company financially for growth,” Romano explains. “No decision has been taken by the board, but we might expect one in the next 12-18 months.”

Emilio Romano is clearly proud of Mexicana. He waxes eloquent about its heritage – the world’s fourth oldest airline, having been founded in 1921, and operated its first international flight the same year (1927) that Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic. Mexicana employed Lindbergh as a pilot, pioneered many of Mexico’s air routes, built several of its airports, flew the first jet service to the USA in a Comet 4C in 1960, and so on. Against this long and illustrious background, surviving 10 years of government ownership is just another chapter.

“This airline has been on the verge of bankruptcy many times and has been the leader many times,” Romano beams. “Through it all, the culture and strength of Mexicana is still there.”

Local talent

When Mexicana appointed Emilio Romano as managing director in March 2004, Jesus Ramirez, president of the pilots union, raised concerns. Not only did Romano lack airline experience, he was filling some very big shoes.

Fernando Flores, his predecessor, had led Mexicana for nine years and had a respected following. By contrast, Romano’s experience was in television and taxes. Relations were off to a rocky start.

They have now improved. The pilots came to realise that Romano’s background as vice-president of international operations at Grupo Televisa brought benefits to Mexico’s largest international airline. The senior positions Romano held in the finance ministry, where he helped negotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Mexico-USA tax treaty, also helped an airline that was expanding into the USA.

And his service with Mexico’s fiscal attorney, where Romano was director of revenue policy and international fiscal affairs, had obvious links to his role at Mexicana. Finally, Romano’s consulting in restructuring and strategic planning may have been for entertainment and media companies, but the pilots saw how those talents also applied to airlines.

Born and raised in Mexico City, Romano earned a local law degree then went on to gain a degree in international law from the City of London Polytechnic. He is married with two daughters.

Click here for more Airline Business interviews

Source: Airline Business