The fifth-generation Lockheed Martin F-35 fighter could have a new engine by the end of the decade.

GE Aviation has been developing a next-generation adaptive engine for the F-35 under a 2016 US Air Force (USAF) contract, as a potential upgrade to the jet’s current Pratt & Whitney F135 powerplant.

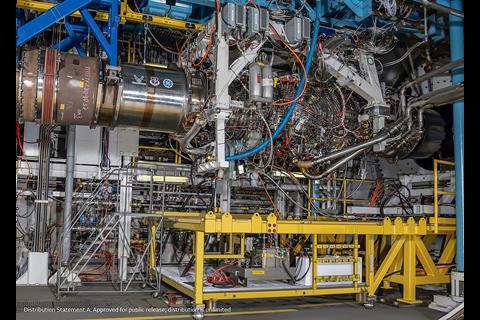

Speaking at the Farnborough Airshow on 19 July, the head of advanced projects at GE Aviation’s Edison Works, David Tweedie, said that his company can have the currently-experimental XA100 engine flying on F-35s by the end of this decade.

“The technology is ready,” Tweedie says. “We have a mature capability that we didn’t have eight years ago,” referring to the start of the USAF’s Advanced Engine Transition Programme (AETP) contract in 2016.

Under that project, both GE and P&W were given $1 billion to fund research and development into producing an improved F-35 engine that could provide greater speed, longer endurance and improved power output for the advanced fighter.

Eight years later, Tweedie says the two working prototypes of GE’s XA100 engine indicate the system could boost the F-35’s range by 30% and give the jet 20-40% faster acceleration. It also offers double the current amount of power for cooling the suite of increasingly powerful on-board electronics.

“This is not an incremental improvement, but a fundamental change”, Tweedie says of the advancements in the XA100. He describing the design as the next evolution in propulsion technology, equating it to the transition from piston engines to turbojets and ultimately to the modern turbofan.

GE made a deliberate choice when selecting XA100 as the engine’s official designation, Tweedie notes.

“This not an F-series engine”, he says, referring to the line of engines that powered such iconic combat aircraft as the Grumman F-14 Tomcat, Boeing F-15 Eagle and the Lockheed F-16 Fighting Falcon.

“This is the first A-series engine”, Tweedie says emphatically.

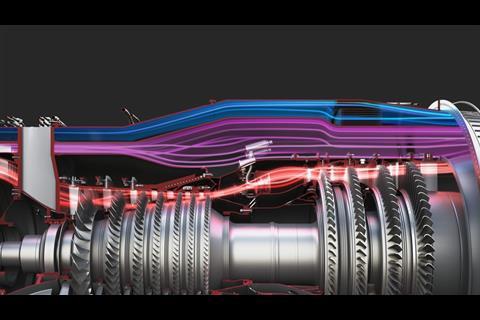

While much of the design remains a secret, GE says what makes it revolutionary is the ability to combine the thrust performance of a traditional fighter engine with the fuel efficiency of a long-haul commercial powerplant.

To achieve this, Tweedie says engineers at Edison Works developed an adaptive system that automatically adjusts the air bypass ratio of the engine while in flight. This allows the aircraft to generate high levels of thrust and acceleration when needed, such as a dogfight, but also operate with much greater fuel efficiency during periods of lower performance demand, like air patrols or long-distance cruising.

The XA100 also incorporates three independent streams of airflow and ceramic matrix composite components with substantially increased thermal tolerance.

While the XA100 was designed under a USAF contract for the service’s fleet of conventional take-off and landing F-35As, Tweedie says GE made the decision to engineer the powerplant to also fit the needs the US Navy’s F-35C catapult-assisted-take-off-but-arrested-recovery (CATOBAR) carrier variant.

The company achieved “100% part number common” engines that can work for both F-35A and F-35C, according to Tweedie, with no need for a structural re-design in either aircraft.

The short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) F-35B variant used by the US Marine Corps presented a greater challenge and is currently not compatible with the XA100, GE says.

However, Tweedie notes that his team is exploring the potential capability improvements, and associated costs, that could come from some day integrating the GE engine into the STOVL F-35.

GE is positioning the XA100 as a potential block upgrade for the F-35 fleet, mid-way through the airframe’s lifecycle run. The company claims that the USAF alone could reap savings of $10 billion in fuel and maintenance costs if the service adopts the engine for its F-35As in the late 2020s.

P&W argues that modifications to the current F135 engine, developed through AETP funding, can improve efficiency and performance at a far-lower cost than a wholesale replacement of the F-35 powerplant.

The company says its F135 Enhanced Engine Package (EEP) can deliver “meaningful propulsion capability” to the F-35, without the technical or cost risks of an entirely new engine.

P&W claims its EEP will result in $40 billion in lifecycle cost savings over the lifetime of the F-35 fleet.

Whatever decision the USAF ultimately makes is likely to be heavily influenced by politics in Washington.

The 2022 National Defense Authorization Act, the law passed by US Congress that governs military spending, required the USAF to develop a “competitive acquisition strategy” for integrating an AETP-derived propulsion system to the USAF’s F-35A fleet, beginning no later than 2027.