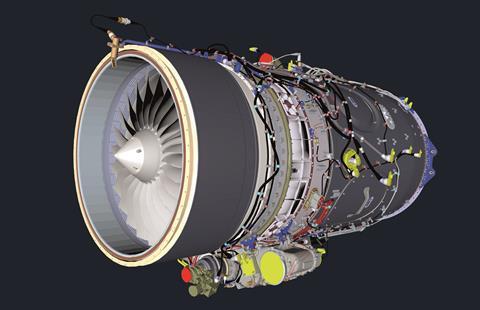

Virtual reality technology that allows students to view the inner workings of an engine using similar animation techniques to those used in the gaming industry is transforming the way engine maintenance is taught at FlightSafety

From Zoom meetings with customers to virtual medical appointments, Covid-19 work-from-home mandates accelerated the advance of a range of technologies that allowed us to communicate, learn and network with each other without being in the same room. Many will continue to prove important long after the virus is history. FlightSafety International’s virtual engine trainer – developed for Pratt & Whitney Canada engine training – is without a doubt one of them.

The Raytheon Technologies company began partnering with FlightSafety International about a decade ago to expand the reach of its engine technical training programmes, to offer best in class customer training and convenience, leveraging FlightSafety’s worldwide reputation.

This partnership evolved through excellent collaboration and resulted in this interactive virtual experience. While the pandemic was not the reason behind its roll out, the difficulty of getting students to training centres meant advantages of the virtual engine trainer became clear in 2020 and 2021. “It has been extremely useful during Covid,” says DeWayne Dixon, regional director for maintenance training, FlightSafety. “It meant our clients had a real teaching aid in their living rooms, and weren’t just looking at a PowerPoint slide.”

P&WC has provided positive feedback on this supplemental way of offering hands-on instruction, which allows students to better understand how to identify internal faults invisible to the eye. You can do lots of things with a real engine, but you can’t insert damage like corrosion.

What is so different about the virtual engine trainer is that it allows instructors and students to really get under the skin of an engine, to view it at individual component level and understand how each part interacts. Engines can be virtually disassembled so units can be “replaced”, while the virtual trainer also simulates an engine inspection during borescope training, where damage or defects can be synthetically introduced deep into the structure – something difficult to do on a real engine. Another advantage in using a virtual engine is when the inevitable product updates occur on a production or legacy engine model, those changes can be incorporated quickly into the virtual engine trainer tool.

The first virtual reality engine was designed at FlightSafety’s Montreal Learning Center in collaboration with the Dallas courseware design team in 2015. There are now 10 virtual engine trainers being used across the FlightSafety network, with another 13 coming in the next 18 months. Many are the popular PT6 variant, but there are also PW200, PW300 and PW800 series engines and soon to arrive PW210, PW100 and PW150 on the horizon.

The interaction is like a video game. The engine itself is set in a virtual workshop, and students click on a part to identify it and move it around. They can also view the engine from different angles or hone in on a particular area. The result is a degree of interactivity and fine detail that is impossible using a physical engine. “It complements what we do in the classroom, but there are situations where it is more effective than the actual asset,” says Dixon. Instructors love it because they can illustrate in real time what they are trying to explain, while it is clear students enjoy the technology because so many of them ask to stay on after the formal session to continue using it. “The feedback has been amazing,” he notes.

“It complements what we do in the classroom, but there are situations where it is more effective than the actual asset”

DeWayne Dixon, Regional director for maintenance training, FlightSafety

Virtual learning will never completely usurp hands-on training using a real engine, not least because regulatory authorities have requirements to use aircraft or engines as part of the practical training. “Even without that requirement, there are going to be times where a hard engine asset is required. It is about a good balance between virtual and hard assets,” says Dixon. “Ultimately, clients will dictate that balance.”

However, he believes the virtual trainer is a “game changer for students and for our instructors” with the ability to teach everything from basic introductions to the engine to very advanced technical courses. “It has helped bring training up to a new level,” he says. “It has really moved the needle for us and for our clients.”