On 1 February, a major relocation and expansion of General Electric's engine icing infrastructure crystallised with the inauguration of a 11,200m2 (121,000ft2) test facility at Winnipeg in Canada's Manitoba province.

|

|---|

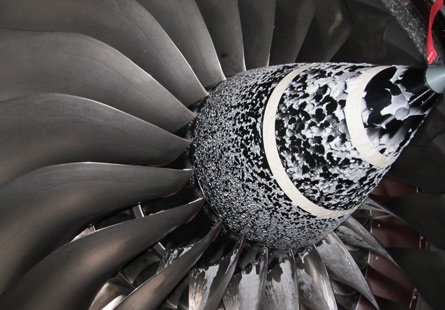

© GE GE's new $50 million icing facility was inaugurated on 1 February |

GE certainly has its hands full, with five new centreline engine development programmes - including three variants of its CFM International Leap-1A, -1B and -1C for Airbus, Boeing and Comac narrowbodies - plus the GE Passport 20 engine for the Bombardier Global 7000 and 8000 and the NG34 for a potential future application in the 70- to 100-seat market.

TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT

That count may soon rise to six, with a possible 90,000-100,000lb (400-445kN) thrust GE9X development for the conceptual next-generation 777X family, for which GE is spending an estimated $50 million on technology development in 2012, says GE Aviation chief executive David Joyce.

"With that many programmes in mind [and] the workload we're going to have in 2013, 2014, 2015, we needed a facility that not only could do icing testing, but could be expanded with... the windtunnel to be able to do hail [and] water ingestion," says Kevin Kanter, GE Aviation's design and system integration engineering assembly, test and overhaul manager.

"We typically we do them all at Peebles [Ohio], which is our primary location, but when you're doing five new centreline engines, you're going to have overlap, and we wanted to make sure we had the flexibility to do it here [in Winnipeg]," he adds. "We can take engines from Peebles, bring them here, run them. Same software programmes, same cables, same everything."

The expansive Winnipeg facility replaces GE's previous Canadian icing facility at Mirabel airport near Montreal, Quebec, which opened in 2006. In July 2010, GE was notified by the airport authority that runs Montreal's Mirabel and Dorval airports that the expanding industrial footprint at Mirabel for the 100 to 149-seat Bombardier CSeries and its Pratt & Whitney PW1524G engines would require relocation of its icing facility.

The cost to locally relocate the concrete pad to maintain the base at Mirabel was viewed as prohibitive, and GE set about finding an alternative. By September 2010, a partnership with StandardAero had been forged, which will allow the aviation services provider to run the facility until 2021.

As part of the agreement, the TDRC will be run by test-cell operators and engineers supplied by StandardAero, which already operates a GE CF34 and CFM56-7B maintenance facility in Winnipeg. The TDRC will initially employ 10 StandardAero employees, says GE, That could grow to 50 by 2017. The facility came together at near-astonishing speed, says Brent Ostermann, programme director of test facilities at StandardAero. Construction began on 26 April 2011 and was completed some seven months later. Full operability is due to be attained in time for the 2011-2012 icing season.

The 6.1m (20ft) centreline single-post thrust stand for engine mounting becomes the fifth in GE's testing arsenal, adding to four at the engine manufacturer's Peebles test facility, and allows the TDRC to accept an engine up to 381cm (150in) and 150,000lb of thrust - a rating designed to contain the energy of a blade-out event for an engine of that thrust.

GE stresses that no turbofan engine exceeds the thrust of the GE90-115BL, which powers the 777-300ER. This reached a top thrust of 127,500lb in testing.

The facility's location in Winnipeg allows GE a longer period each year in which to conduct icing tests, which require a temperature range between -4˚C and -20˚C.

|

|---|

© Jon Ostrower/Flightglobal GE partnered with StandardAero to develop the facility |

Compared with the Quebec facility, Winnipeg's unique climate conditions expand the potential icing window by "at least a month", widening Winnipeg's icing calendar from Mirabel's November to March each year to, potentially, as long as October to April, says Kanter. The Mirabel site "was not capable of running year-round. For one, the windtunnel was fixed, so now we made it move axially, so we can move it out of the way", he adds.

The axial translating "free jet" windtunnel system and its 125-nozzle icing array is mounted on 134m of rails. This enables testing beyond icing and cold weather evaluations, providing a site for engine endurance, hail, bird ingestion and mixed-phase testing.

GE's free-jet system differs from Rolls-Royce and Pratt & Whitney "direct connect" icing systems that connect the windtunnel directly to the bellmouth of the engine.

NOISE ATTENUATION

To maintain a noise-neutral sound level at the airport, the new Winnipeg site features an extensive noise attenuation system, including 15.2m-tall blast deflection walls, 4.9m diameter engine exhaust augmenter and a 15.5m vertical stack. The facility costs an estimated $1 million per month to run, says Kanter, with power needs estimated at around 2MW of electricity.

At the time of its inauguration, the first shakedown engine - a Performance Improvement Package One (PIP1) model GEnx-1B engine for the Boeing 787 - was nearing its mounting on the test stand for final calibrations and qualifications of the site before its first certification icing trials on the GEnx-1B PIP2 configuration.

The icing certification was expected to be completed within four weeks of its commencement in mid-February or less than that with the right weather conditions.

Final US Federal Aviation Administration Part 33 certification for PIP2 is expected to be granted to GE in June, clearing the up-to-78,000lb engine for airframe certification and service entry on the 787-8 in 2013.

Following the PIP2 icing trials, the facility is also likely to be used for testing the GE Honda HF120, which powers the HondaJet, later this year, and for additional engine endurance testing, says Kanter.

GE is also developing a PIP for the GEnx-2B engines that power the 747-8 and -8F, pulling from changes first designed for the GEnx-1B's PIP2, which modifies the engine's high-pressure compressor.

Kanter says the certification testing being run in February on the PIP2 engines may dually apply to the GEnx-2B's PIP: "They may not have to run icing on it; they're hoping that the certification that we get here on the PIP2 [GEnx-1B] programme will carry over, but if it doesn't we're ready to bring an engine next year up here."

After the conclusion of the 2012 icing season, GE will shut the facility down for testing for a planned construction period, in which it will build support facilities for servicing the engines on-site, as well as establishing a permanent power connection in time for the 2013 season.

BREAKING THE SEAL ON NEW ICING TESTS

Traditionally, Rolls-Royce has performed icing tests in the limited environment of an altitude test facility. For the Trent XWB, the company used the purpose-built "Glacier" facility in Manitoba, built in partnership with Pratt & Whitney. The XWB tests were the first to be carried out at this facility, enabling the manufacturer to conduct more testing in different conditions than ever before.

"One of the things you really want to do when you've done all of the ice build up - to understand how your engine operates when it's icing - is to shut the engine down and get in there, get lots of cameras out and see where the ice has built up," says Trent XWB programme director Chris Young.

|

|---|

© Rolls-Royce The Trent XWB tests were the first at the new facility |

The chamber at an altitude test facility is a sealed vacuum, which makes it difficult to gain access to the engine before the ice melts. For the XWB tests at the Glacier facility, Rolls-Royce generated six mandated certification conditions for icing, plus another 12 icing test points for its understanding and maturity purposes.

The tests determined a "very minor" compressor blade redesign was required, expected to be completed in time for the start of Trent XWB flight testing. As a direct result, it will be possible for the A350 to dispatch with its engine anti-icing system inoperable if required.

Source: Flight International