If you had asked an Embraer executive in early 2010 what the Brazilian manufacturer's next commercial aircraft would be, the answer would probably have been a clean-sheet small narrowbody with a five-abreast cabin seating between 100 and 150 passengers.

In 2010, Embraer was only 15 years removed from the first flight of its ERJ-145 – the 50-seat regional jet that catapulted the small Brazilian manufacturer to becoming the world's third-largest producer of commercial aircraft. The arrival of the original E-Jet family nearly a decade later established the company as the world's dominant supplier of large regional jets.

As Embraer's ascent proves, the aviation world moves quickly. By 2010, the company was already looking beyond the E-Jet family. At the time, Airbus had not yet launched the re-engined A320neo family. It was widely believed that Airbus and Boeing were ready to vacate the market for aircraft under 150 seats and launch new single-aisle types to replace the A320 and 737NG families. Bombardier – Embraer's bitter rival in the regional jet sales competition – had already bet heavily on such an outcome in 2008, launching the 100- to 140-seat CSeries family.

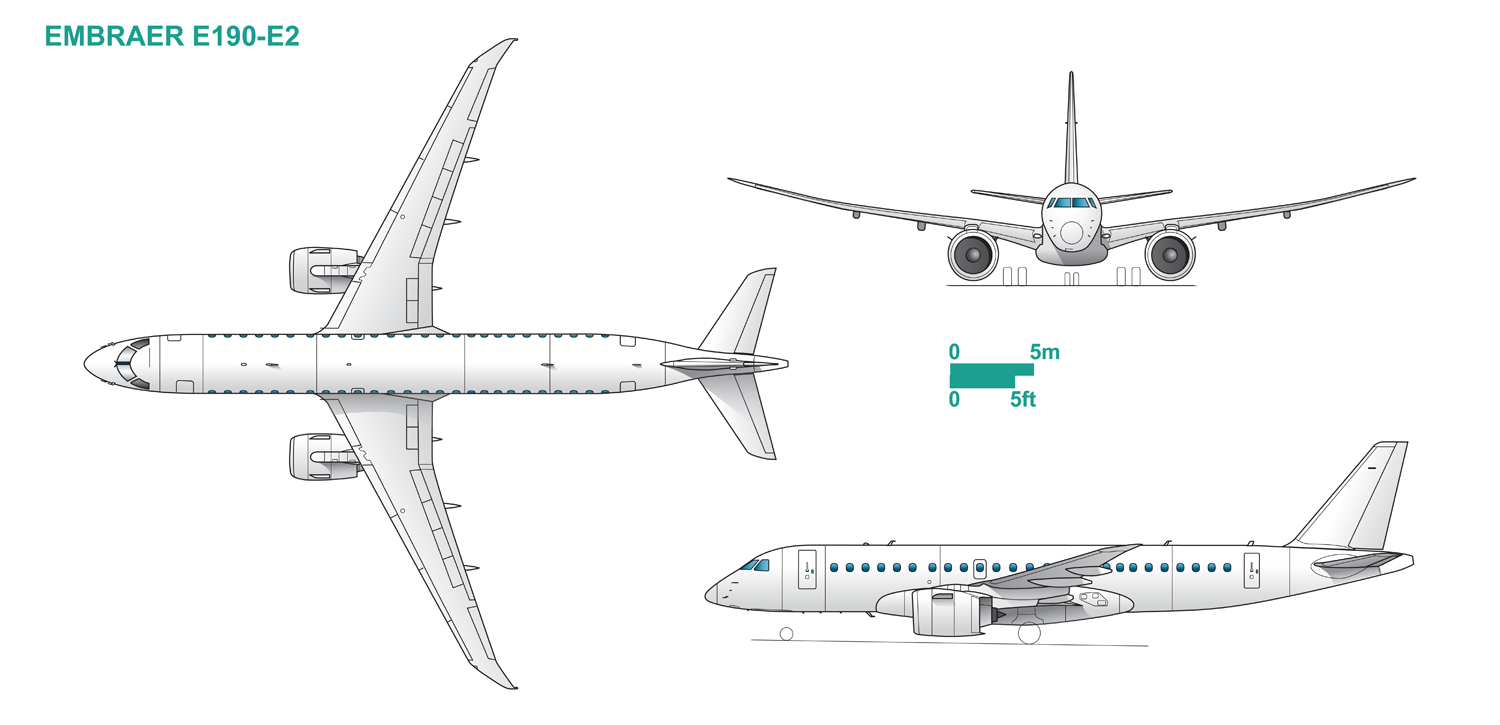

Embraer's E-Jet upgrade features new engines, larger wings and empennage, and a full fly-by-wire control system

Embraer

Embraer was also facing increasing competition in the large regional jet market. In addition to Bombardier's series of stretched variants of the 50-seat CRJ200, new competitors in China, Japan and Russia were developing new regional jets in an increasingly crowded 70- to 130-seat segment.

But then the market shifted again. Rather than vacate the sub-150-seat segment as expected, Airbus launched the A320neo family in December 2010, including the 124-seat A319neo. Boeing Commercial Aircraft initially snubbed Airbus's decision. Four months later, then-president and chief executive James Albaugh publicly predicted his company would never re-engine the 737.

Only a few months later, the A321neo scored a massive new order from stalwart Boeing customer American Airlines. Boeing launched the re-engined 737 Max a month after that.

Embraer quickly returned to the drawing board. With Airbus, Boeing and Bombardier now crowding the market for small, narrowbody aircraft, the Brazilian airframer would decide within a year to keep its focus on the large regional jet market.

So Embraer committed to a new plan on the eve of the Dubai air show in November 2011. Instead of directly challenging the CSeries with a clean-sheet development programme, Embraer launched an extensive revamp of the E-Jet family. This would be no A320neo-style re-engining project, with only the propulsion system replaced to improve fuel efficiency, however.

EVOLUTIONARY STEP

In addition to installing new engines, the E-Jet E2 family, led by the 97-seat E190-E2, would feature larger wings and empennage surfaces, plus a second generation of Honeywell's Primus Epic integrated cockpit and a Moog-supplied, closed-loop full fly-by-wire control system.

After launching the E-Jet E2 family in June 2013, Embraer has kept the development of the E190-E2 on schedule. The manufacturer rolled out the first flight-test aircraft from its factory in Sao Jose dos Campos in February 2016 and flew the aircraft three months later. By the end of the second quarter of this year, Embraer confirmed, the first E190-E2 had completed 80% of certification testing and was on track for delivery to its launch customer – Norway's Wideroe – in April 2018.

Embraer says the PW1900G accounts for 11 of the promised 16 percentage points of improvement in fuel efficiency

Embraer

Six years ago, Embraer's designers faced the difficult question that arises with any re-engining project: how to preserve enough commonality to keep the re-engined type attractive to existing customers, yet insert enough new technology to keep competitors at bay and expand the type's appeal to new customers.

"Our strategy is to improve and evolve the E2 and stay in our segment, but keep the leadership in our segment," an Embraer manager tells FlightGlobal. "We want to grow at the same time. So we had to do a design that would allow us to change the balance between this type of aircraft and the narrowbodies."

The manufacturer believes the market for large regional jets will continue to grow, its latest market forecast shows. "Embraer foresees world demand for 6,400 new jets in the 70- to 130-seat segment over the next 20 years – 2,280 units in the 70- to 90-seat segment and 4,120 units in the 90- to 130-seat segment – representing a total market value of $300 billion," the forecast reads. "The 70- to 130-seat jet world fleet in service will increase from 2,700 aircraft in 2016 to 6,710 by 2036, the fastest-growing segment among all aircraft categories."

To start, Embraer believed some pruning of the E-Jet family was in order. The smallest member, the 70-seat E170, did not survive the cut. The E175-E2, meanwhile, was stretched by 0.72m (2.4ft), adding a row of four seats. Embraer also stretched the E195-E2 by 2.85m, adding three rows with 12 seats.

The length of the E190-E2, however, remained unchanged. The aircraft already seats 96 passengers, and any revenue benefit to an airline by extending the length to add another four seats would backfire, as international operating regulations would require the carrier to add another flight attendant for any capacity over 99 seats. As a result, the E190-E2 will enter service with a familiar-looking fuselage, both in terms of length and width.

Click here to buy this cutaway

In terms of fuselage width, the E190-E2 remains an outlier among its peers. Whether counting historical aircraft, including the Fokker 100 and BAe 146, or modern competitors, such as the Antonov An-148, Comac ARJ21 or Sukhoi Superjet, aircraft designers have consistently chosen a cabin with five-abreast seating for the large regional jet market. The original E-Jet proved that a four-abreast cabin was not only viable but could dominate the segment.

The geometry of the four-abreast cross-section does not appear to work in Embraer’s favour, however. Instead of a circular cross-section favoured for five-abreast seating, Embraer selected a "double-bubble" shape: two stacked ovals pinched at the floorboard of the passenger cabin. Such a geometry reduces the frontal area of the fuselage, but increases the wetted area, as the cabin's reduced width is offset by the extra length.

Embraer also makes no apologies for delivering, in 2018, a new commercial aircraft with a standard aluminium alloy fuselage and wing. "Our airplane is metallic, not an expensive composite wing or aluminium-lithium fuselage. We are very weight-efficient," says Embraer commercial chief operating officer Luis Carlos Affonso. The E-Jet E2 family is also efficient to build, as Embraer can take advantage of a mature production system.

But the similarities do not even run skin-deep, as a quick scan of the sales brochures of the E190 and E190-E2 demonstrates. Compared with the original model, the E190-E2 is listed with a maximum take-off weight nearly 8.9% higher, at 56,400kg (124,300lb). Curiously, the E190-E2's maximum fuel load is only slightly greater, at 13,300kg, but the range of the aircraft leaps by 16%, to 2,850nm (5,280km).

ENHANCED MODEL

A significantly higher range and a similar fuel load suggest significant improvements made to the aircraft's aerodynamics or propulsion system. In the case of the E190-E2, the answer is both. The E190-E2 features a completely new wing that is both longer and thinner than the original. In fact, wing area for the E190-E2 is 10% higher and its aspect ratio is greater by 23.8%. Embraer estimates that the new metallic wing improves the E190-E2's fuel efficiency by 3.5% compared with the original E190.

The significance of the E190-E2's new wing is surpassed in importance for fuel efficiency only by Embraer's choice of propulsion systems. The company received bids in 2012 from GE Aviation, Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce. The UK engine maker provided Rolls-Royce AE 3007 engines for the ERJ-145 regional jet, while GE supplied the CF34-10Es powering the original E-Jets, and offered an engine featuring the same technologies applied in the high-pressure core of the CFM International Leap engine. In the end, Embraer decided to change suppliers again and selected P&W's PW1900G geared turbofan.

As a derivative of the geared turbofan originally fielded with the CSeries, the PW1900G represents a major leap, as it were, over the original E-Jet's 1980s-era CF34-10E. With a 1.85m (73in) diameter fan – more than 7.5cm wider than the Leap-1B engine for the 737 Max – the PW1900G is designed with a 12:1 bypass ratio, using a reduction gear to decouple the rotation speed of the fan relative to the low-pressure turbine in order to prevent the fan blades from spinning faster than the speed of sound.

P&W is still working to improve the durability of the engine and meet production ramp-up targets for the CSeries and A320neo family, but the fuel efficiency of the geared turbofan architecture has met expectations. The effect could be even more pronounced with a geared turbofan installed on the E190-E2. The 12:1 bypass ratio of the PW1900G compares well with the 5.4:1 ratio available on the CF34-10. Embraer estimates that the PW1900G accounts for 11 of the promised 16 percentage points of improvement in fuel efficiency between the E190-E2 and an early version of the original E-Jet.

The improvement in specific fuel consumption does not come without a price. A heavy – literally – penalty in weight must be accounted for. P&W certificated the PW1900G with the US Federal Aviation Administration with a listed weight of 2,180kg: a roughly 5% increase compared with the CF34-10E. With a 48cm increase in fan diameter compared with the GE engine, the PW1900G also required Embraer's designers to increase the length of the landing gear. The E190-E2 stands about 40cm taller than its predecessor.

Other changes to the aircraft's aerodynamic surfaces are a result of arguably the E190-E2's most important feature: fly-by-wire.

It is true that Embraer fielded the original E190 to JetBlue in September 2005 with a fly-by-wire system, but it was only partial, controlling the rudder alone. Over the next decade, Embraer became immersed in the challenges of integrating a full fly-by-wire system on an aircraft. The company's development began with the fielding of the Legacy 500 and 450 business jets. That was followed by the development of the KC-390 tanker/transport, which entered development in 2009 but will enter service a few months after the E190-E2. As a result, the E190-E2 becomes the third generation of Embraer aircraft using full fly-by-wire.

As the first such re-engining project, the E190-E2 offers a vivid glimpse of one of fly-by-wire technology's least appreciated benefits. The use of fly-by-wire control laws to improve safety by imposing a set of flight envelope protections is well known. A less celebrated benefit is the opportunity it gives aircraft designers to move the centre of gravity of the aircraft slightly rearward. As the location shifts, the job performed by the horizontal stabiliser – counteracting the tendency of the nose to pitch up – gets easier. As a result, Embraer can reduce the size of the stabiliser slightly, with corresponding declines in weight and drag.

Embraer advertises the E190-E2 as the "profit hunter". With a high-aspect-ratio wing, geared turbofans and a full fly-by-wire system, the second-generation E-Jet can, its manufacturer foresees, go beyond the traditional role of the regional jet. Instead of feeding passengers from secondary airports into central hubs, the E190-E2 is designed to deliver profits on point-to-point routes with US transcontinental distances.

So far, in terms of market reaction, the E190-E2 has been slow to mature. Embraer launched the E-Jet E2 family more than four years ago, but the flagship E190-E2 has amassed only 83 orders, including an order for 20 aircraft from now-defunct carrier Air Costa. That amounts to a backlog of less than a year at Embraer's current production rates for the original E-Jet.

With entry into service five months away, Embraer still has time to make its case.

"The E190-E2 is about 10% smaller than the [Bombardier] CS100, so you could expect a 10% higher cost per seat, but it's only 3% and 6% lower cost per trip," Embraer says. "So if you don't need all those seats [of the CS100], the 190 is the best solution."

Source: Cirium Dashboard