With hydrogen technology finally on the horizon, Marshall Chief Growth Officer Bob Baxter explains how the UK can seize a once-in-a-generation chance to shape the future of flight – and reap the benefits from doing so

Engineers and industry commentators used to joke for decades that “hydrogen will forever be the fuel of the future”. Some may still repeat this line, but these days it doesn’t get the laughs it used to.

There is a growing consensus across sectors and industries – and particularly within aviation – that the widespread use of hydrogen as an energy vector is becoming technologically and commercially feasible. This shared sense of informed optimism is the result of breakthroughs around production, storage, conveyance and fuelling of hydrogen – as well, of course, as advances in powertrain technologies.

The retreating scepticism has exposed a rich vein of opportunity, sparking a rush of private and public investment that will only benefit those who have built up the right resources, knowledge and expertise. Capitalising on this opportunity is, in theory, optional, but missing out will have consequences – for private sector players within industry, but also for governments looking to claim and maintain their stake in the future of energy and transport.

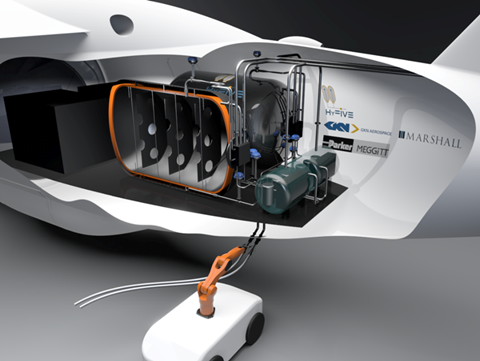

As the lead partners of HyFIVE, a newly announced UK consortium spearheading hydrogen fuel system development, Marshall understands that the necessary investments and potential rewards from hydrogen will extend far beyond the tactical: UK PLC must seek to unlock long-term benefits in terms of jobs, skills, investment, intellectual property, exports and homegrown supply chains.

Growing the UK’s international competitiveness

Hydrogen is set to become one of the world’s most fiercely contested intellectual property battlegrounds. With time in increasingly short supply, it is critical to act quickly and place the UK at the forefront of the emergent hydrogen economy through a balanced approach to academic and industrial involvement, with support from government.

This is why the HyFIVE consortium, while led by industrial partners Marshall, GKN Aerospace, and Parker Meggitt, has also recruited three of the UK’s top research hubs for specialised R&D around cryogenic hydrogen technology: the University of Manchester, the University of Bath, and Cardiff University.

With the backing of robust government policy, industrial-academic partnerships such as HyFIVE will ensure that the UK builds and maintains a “moat” of sufficient breadth and depth to safeguard its IP leadership for years to come.

Hydrogen is also an unprecedented opportunity to export UK-made products and services to the rest of the world; after all, the total accessible market for hydrogen in aviation is expected to stand at nearly £60 billion by 2050, with fuel systems accounting for over half of this. The sheer scale of hydrogen in aerospace will benefit exporters as much as it penalises importers. Belonging in the latter column should not be an option the UK is considering.

Additionally, fostering healthy domestic production of hydrogen fuel systems and powertrains for export will have a considerable knock-on effect throughout the UK’s aerospace industry, likely bringing production of other aircraft components to our shores.

A new generation of jobs and skills

Aerospace technologies may have progressed rapidly over the last few decades, but advances in the core technologies powering flight have been largely incremental. Hydrogen changes this, presenting our industry with a genuine technological inflection point – and with it, a host of challenges.

Naturally, hydrogen will not immediately replace conventional fuel stocks – but it will create demand for new jobs and new skills, and the UK must be ready to meet this demand.

From the perspective of our own consortium alone, we estimate that successful exploitation of HyFIVE technology with government support could lead to the creation of 2,500 manufacturing jobs in the UK by 2050, in addition to hundreds of R&D jobs within the same timeframe.

While the hydrogen economy is set to create new jobs, it will also require extensive adaptation to new skills and training standards. In an industry already facing a severe skills gap and an aging workforce, this poses both a potential hurdle and an opportunity to train a new generation of talent.

First, we must ensure that training providers are provided with insights around the kind of people we expect to need over the coming years. Secondly, we must guide the evolution of apprenticeship standards and degree courses around hydrogen, while also supporting the creation of dedicated training centres at hubs throughout the new hydrogen ecosystem.

Again, this is something that can only be achieved through industry-academia collaboration. This is why we designed HyFIVE with a view to creating a UK-wide footprint of core partners with training facilities spanning from Bath, Bristol, and Cardiff to Cambridge, Manchester, and beyond. Over the coming years, with further support from government, we expect to expand this hydrogen knowledge network to academic centres of excellence throughout the UK.

Boosting investment

Beyond exports, IP, jobs, skills and training, hydrogen is set to supercharge domestic investment in facilities and R&D, while sparking demand that can be satisfied by a nationwide supply chain comprising large and small businesses alike.

For example, Marshall, GKN, and Parker Meggitt expect that the HyFIVE project alone will generate millions of pounds in further UK spending following completion, much of which will come from additional R&D by consortium partners. Writ large, the economic impact of hydrogen within UK aerospace and adjacent sectors could be orders of magnitude greater.

More generally, the existence of a consortium like HyFIVE will foster the growth of a cryogenic hydrogen supply chain in the UK. Even based on our initial consultations with potential subcontractors, we have already seen how aerospace suppliers are now preparing to upskill in cryogenics and hydrogen, while suppliers on the cryogenic science and medical side of the fence have equally started looking towards potential new business in aerospace.

This trend will stand to benefit SMEs across the UK – particularly those with highly specialised capabilities that can be adapted at low risk to capitalise on the new opportunities presented by hydrogen.

Seizing the chance

It is tempting to see the struggle for technological leadership in a frontier domain like hydrogen as a vanity exercise, with the only downside of not competing being a loss of face on the international stage.

In reality, hydrogen is a must-play game whose outcome could revolutionise our knowledge economy, spur nationwide growth, and ensure our continued relevance – and prominence – in the aerospace and energy sectors.

This is an outcome that will only be achieved if likeminded industry partners join forces to collaborate in a manner that enables each to play to their strengths. Likewise, leading academic research groups must be granted an equal seat at the table to guide the development of technologies and products by sharing their specialist knowhow. Lastly, support from government is an essential catalyst that will lower barriers to entry, reduce the risks of collaboration, drive the creation of new skills and training standards, and set a consistent set of targets for industry and academia to collectively aspire to.