India has displaced China as the global aerospace industry’s growth frontier, with a bigger orderbook and a more welcoming economic and geopolitical outlook.

Air India’s recent commitment for 470 Airbus and Boeing jets is set to be one of the year’s biggest aviation stories. Despite the hype around the deal, including a call between US President Joe Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Air India’s statement referred only to “letters of intent” with the two airframers. Boeing said its aircraft had been “selected.” Airbus said Air India had made a “commitment to order.”

When, exactly, things will be finalised is not clear, but the Air India commitment highlights the shift toward India’s becoming the most important emerging market for Airbus, Boeing and the broader global aerospace sector.

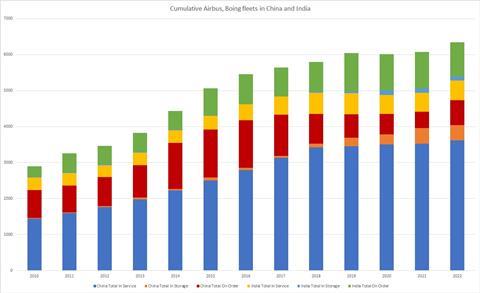

For decades the top market was, by a long shot, China. Chinese airlines still have far more in-service Boeing and Airbus aircraft than India.

At the end of 2022, there were 3,621 Airbus and Boeing flying in China, compared with India’s 551, according to Cirium fleets data. If in-storage aircraft are counted, China’s cumulative Airbus/Boeing fleet was 4,044 strong, compared with India’s 664.

On firm orders with Airbus and Boeing, however, Indian airlines eclipsed Chinese airlines in 2019, when low-cost carrier IndiGo ordered 300 A320neo family jets. At the end of 2019, Indian carriers had firm orders with Boeing and Airbus for 1,063 aircraft, compared to China’s 655.

In July 2022 China’s “Big-Three’ state-owned carriers – Air China, China Eastern Airlines and China Southern Airlines – helped narrow the gap with an order for 292 A320neos, but at the end of the year Indian carriers still held more orders. Were Air India’s 470 aircraft order firmed up today, the Indian order lead would widen further.

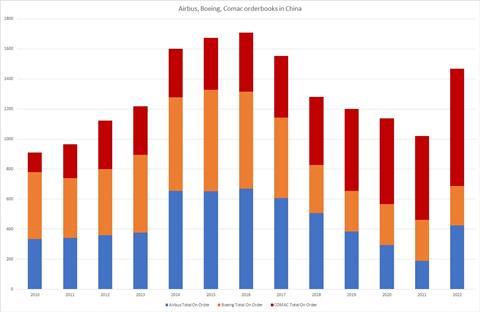

It is key to note that Chinese state-owned airframer Comac had 782 firm orders from Chinese carriers at the end of 2022, more than the 687-aircraft combined orderbooks of Airbus and Boeing. Of these, over 500 are for the C919, built as a straight-up rival to the A320 and 737 families. The type is on the verge of entering revenue service in China.

While China certainly remains pivotal to Airbus, Boeing, and the other big aerospace firms, the high level of Indian orders illustrate the strong tailwinds driving the Indian economy.

Demographically, India is in a far stronger position than China. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), India’s population is 1.42 billion, thus surpassing China’s 1.4 billion. Most significantly, India’s population is young. The Pew Research Center suggests that over 40% of its population is under 25, with an Indian median age of 28, compared with China’s median age of 39.

As China’s population gradually ages and shrinks, bedeviled by a low birthrate, the country is unlikely to re-experience the economic boom that drove it to become the world’s second largest economy – and to place the bulk of the world’s aircraft orders. India, by comparison, looks set to enjoy significant economic growth in the 2020s and beyond – good news for airlines and aircraft manufacturers.

Apart from the growth of India’s airlines, India has significant potential to be more involved in the global aerospace supply chain. Indeed, the Modi government, seeing the billions going to Airbus and Boeing, is likely to demand more participation for Indian industry.

To take advantage of China’s growth, Airbus set up an assembly capability for the A320 family in Tianjin in association with the Tianjin Free Trade Zone and Chinese state airframer AVIC. An A330 completion and delivery centre was set up in 2017. Boeing has a joint venture with Comac for 737 Max completions.

These high-profile commitments on the commercial side are more substantial than anything either manufacturer has done in India thus far – although Indian companies are involved in the supply chains for both Airbus and Boeing types.

Indian workshare on defence projects underlines the clear potential for Indian companies to play a greater role in commercial aircraft manufacturing. Companies such as Airbus, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin have considerable partnership footprints in India. These stem from Indian defence offset policies, which generally require 30% of the value of defence acquisitions to be plowed back into India, ostensibly to help Indian industry move up the value chain.

A major player in this area happens to be Tata Advanced Systems (TASL), a sister company of Air India in the Tata Group conglomerate. Airbus Defence and Space and TASL are going to collaborate in the local production of 40 C295 tactical transports. The Tata Boeing Aerospace joint venture produces fuselages for the AH-64 attack helicopter.

New Delhi also has a competition for 114 advanced fighters, which includes a requirement for local assembly. Boeing, Dassault, Lockheed, and Saab have all talked up their eagerness for indigenous production.

Moreover, Bengaluru-based Hindustan Aeronautics is active in the global aerospace supply chain, and has a long history of license production, including the BAE Hawk 132 and the Dornier 228.

India’s growing aerospace prominence come as concerns about China have sharpened.

One persistent worry is Beijing’s position as the world’s greatest perpetrator of industrial espionage. In July 2022, the counterintelligence agencies of the United Kingdom and the USA issued a warning about the risk the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) presents for western businesses, citing specific examples in the aerospace sector.

In November 2022, a Chinese spy was sentenced to 20 years in US prison for attempting to steal GE Aerospace trade secrets related to composite materials. The US Federal Bureau of Investigation has a special webpage dedicated to the “China threat.”

Further, Beijing has made no secret that it aims to reduce its reliance on overseas suppliers in sensitive sectors such as aerospace. It is unclear if the C919 is as capable as the A320neo or 737 Max, but Beijing will oblige Chinese airlines to buy the aircraft irrespective – hence the unproven type’s massive domestic orderbook.

For now, the C919 is all but entirely reliant on western suppliers, but Beijing hopes to change this, most notably through the development of the indigenous CJ1000A engine.

Geopolitics can no longer be dismissed. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – which Beijing has tacitly supported – has shown that major military conflicts are still an all-too-real threat. In recent years China has invested in a massive arms buildup and become increasingly aggressive towards neighboring Taiwan. In addition to being a catastrophe for the world, any great power conflict over Taiwan would be a mortal blow for the China businesses of European and US aerospace companies.

On an industrial level, the deteriorating relationship between Beijing and Washington DC likely played a major role in the extended grounding of the 737 Max in the Mainland. Chinese carriers have also yet to commence deliveries of 737 Max jets – although the aircraft is at last flying again in China. After the Chinese order for 292 A320neos, Boeing chief executive Dave Calhoun hinted that geopolitical tensions had affected the deal.

These concerns, in addition to changing Chinese aircraft order policy, serve to diminish China’s role in aerospace – and also oblige chief executives to explore other alternatives for overseas investment and joint ventures. India is a likely beneficiary.

India, to be sure, has its share of challenges. Bureaucracy and Infrastructure are perennial issues, as is corruption. New Delhi also harbours dreams of producing its own commercial aircraft, though the realisation of such an effort is years away. Nonetheless, it’s favorable demographics and growing economy – both former hallmarks of China – make for an unparalleled opportunity for global aerospace.