As Embraer closed out the Dubai air show last week, executives from across its business units gathered in New York City to explain why they think their company is on the cusp of a major rebound.

The air show had been a quiet one for Embraer, which did not announce any new orders at the event. But the executives insist Embraer’s time is near.

They say demand for E-Jets is lagging a broader boom for larger aircraft like Airbus and Boeing narrowbodies. Soon, they say, airlines will turn more attention to E-Jets to fill a market-segment gap.

The executives also say Embraer is returning to financial health, fixing a troubled supply and production system and positioning itself to develop future low-emission passenger aircraft.

“The first wave has focused on the biggest aircraft – the big narrowbodies,” Embraer chief executive Francisco Gomes Neto says on 17 November in New York. “Now, we believe it is coming – a wave to focus on our segment.”

That segment not only encompasses the regional jet market, which Embraer controls with E175s, but also the wedge between regional jets and larger narrowbodies, which Embraer fills with E190-E2s and E195-E2s.

That wedge has long been a tough spot to compete. Airbus and Boeing target the sector with the smallest versions of their best-selling narrowbodies: the 110-160-seat A319neo and 138-153-seat 737 Max, which has yet to be certificated. But neither of those jets have sold particularly well.

“The Max 7 and A319neo – those aircraft are a lot less efficient” than E-Jet E2s, says Embraer Commercial Aviation chief executive Arjan Meijer. “Operators are looking for a much-more-efficient aircraft in the segment”.

Airbus also competes with its A220 family of aircraft, the largest variant of which – the A220-300 – has proven a strong seller. But Meijer views A220-300s as sitting in the same segment as the larger narrowbodies, and therefore competing less directly with E-Jets.

Embraer has enjoyed sales success for its E2s, holding unfilled orders for 174 E195-E2s and 16 E190-E2s at the end of September, according to its most recent figures. Customers include Air Astana, Air Peace, Azul, Binter Canarias, KLM Cityhopper, Luxair, Porter Airlines, Royal Jordanian, SalamAir, Scoot, SKS Airways, Swiss and Wideroe.

“Yes, we need some bigger names on the programme and we are working on that,” says Meijer. “We are expanding the operator base and we see some very good signs that airlines are appreciating the value of the E2 versus the bigger narrowbodies.”

Airlines increasingly “see the E2 not as a regional jet but… a small, versatile narrowbody,” adds Gomes Neto. “We are now in the harvest season.”

By “harvest season”, Gomes Neto means Embraer is ready to reap benefits from transformative work completed in the last few years.

STANDING ALONE

Things were not supposed to have been this way for Embraer. Until early 2020, the company was on track to sell its commercial aircraft division to Boeing, creating a powerhouse. Executives said the combination would give Embraer engineering heft needed to embark on major new development programmes, and let Boeing fill a gap in its product lineup.

In short, the deal was to help both companies better compete with Airbus, which had recently fortified itself by acquiring Bombardier’s CSeries programme, now called the A220.

But the Boeing-Embraer combo collapsed when Boeing unexpectedly backed out in April 2020, leaving Embraer scrambling to adjust.

The company quickly embarked on efforts to improve production speed and efficiency, and to trim costs. It hired Toyota to provide manufacturing consulting and adopted new technologies, including those using artificial intelligence.

Embraer now employs “more than 100 engineers dedicated to cost-reduction activities. This has helped us to mitigate this inflationary impact”, Gomes Neto says.

“We have a potential to grow production and revenue substantially in the next few years.”

Embraer generated revenue of $4.5 billion in 2022. Its revenue is on track to jump 20% this year and another 20% in 2024, and could hit $10 billion by 2030, Gomes Neto says.

The company is rebounding financially. Though it lost $34.5 million in the first nine months of 2023, Embraer swung to a $64.3 million profit in the third quarter. It delivered 105 aircraft (39 commercial and 66 business jets) in the first three quarters of the year, up from 79 (27 commercial and 52 business jets) one year earlier.

Executives said in December they still expect Embraer will hit its 2023 delivery and financial targets – notable because other major aerospace manufacturers recently revised expectations downward, citing factors including a still-struggling supply chain.

Embraer’s 2023 goals including delivering 65-70 commercial aircraft and 120-130 business jets, generating $5.2-5.7 billion in revenue and posting a 6.4-7.4% operating profit margin.

But hitting those targets, particularly the delivery goal, will not come easy amid current supply chain troubles. Embraer’s executives say their output has been hampered by parts shortages, including shortages of the Pratt & Whitney (P&W) PW1900G geared turbofans (GTFs) that power E2s.

“It’s not only engines… We still have bottlenecks with other parts, other equipment,” says Gomes Neto without specifying other components. “We still will… have some difficulty in 2024 because the supply chain is not stable yet.”

Competitors Airbus and Boeing have likewise cited engine shortages as limiting their production.

The engine crunch grew more acute recently because P&W is recalling GTFs for inspections and replacement of high-pressure disks, a result of potential defects due to a powder-metal manufacturing problem. The issue affects more than 1,000 PW1100Gs, which power Airbus A320neo-family jets, and will require hundreds of those aircraft to be grounded at any given time in the coming year.

P&W has said other GTFs, including the A220’s PW1500Gs and E2’s PW1900Gs, are affected by the issue. But it has insisted those aircraft will suffer far less operational disruption.

Meijer says PW1900Gs came to market later and with a “higher standard” than other GTFs. “Because the [E2s are] lighter, the stress – the wear and tear on the engines – is a lot less,” he adds.

Still, some PW1900Gs must be removed from service earlier than initially planned due to newly required inspections at 4,000 to 5,000 cycles, Meijer says. He adds that new PW1900Gs “don’t have the powder-metal issues. They have full life-limited parts”.

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Executives also discussed Embraer’s future, though where its aircraft development will head next remains unclear.

The company still has an E2 version of its E175 on the books, but pilot contracts in the USA prohibit most US regional carriers from operating the type, making it a no-go in the world’s largest market. For that reason, Embraer has said it may continue producing first-generation E175s into the 2030s. And E175s keep selling, with SkyWest Airlines ordering 19 of the type and American Airlines ordering 11 this year.

Embraer had in recent years also floated development of a new turboprop with 70 to 90 seats. The company estimates airlines will need more than 2,200 new turboprops through 2042.

All along, executives insisted Embraer needed partners to assist with such a project, and in December 2022 Embraer said it had delayed deciding whether to launch the turboprop. It said suppliers – specifically engine makers – were unable to meet Embraer’s goals for the aircraft.

“We’ve been very clear to the market that we don’t have an engine for the platform,” Meijer says on 17 November.

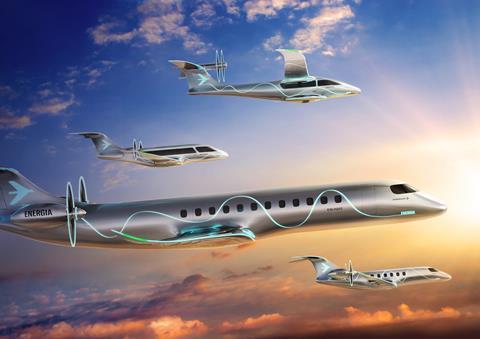

Pressed about Embraer’s next moves, Meijer points to its Energia family of reduced-emission passenger aircraft concepts. But he stresses that Energia remains in early development and evaluation stages and that Embraer has not determined if the project is viable.

“We are very actively looking at Energia,” Meijer says. “This is clearly a lot earlier in the development phase” than the turboprop.”

Revealed in 2021, the Energia programme includes several conceptual aircraft: two hybrid-electric types (the 19-passenger E19-HE and 30-passenger E30-HE) for service for service entry no sooner than 2030, and two hydrogen-fuel-cell powered aircraft (the 19-seat E19-H2FC and 30-seat E30-H2FC) with readiness around the mid-2030s.

Embraer executives recently said they were considering scaling up the concepts to have 50 seats.

Airlines clearly want low-carbon aircraft, and Meijer says many suppliers have expressed eagerness to support the Energia programme.

But interest does not make a business case. Many questions about the high-cost project remain unanswered, including whether it even makes sense, says Meijer, adding that small passenger aircraft have long proved a difficult market segment. After all, no 50-seat regional jets remain in production.

“What’s going to be the cost levels of these aircraft if we bring these new technologies onboard, and can the airlines actually make money?” Meijer says. “What are airlines going to do in the future with a 19- to 30-seat aircraft?… Where will the green hydrogen come from?”

Embraer is seeking answers, conducting internal research and discussing Energia with advisory boards composed of airline representatives.

“That’s why we’re talking about concepts and not about clear products,” Meijer says.