CFM may have had some glorious yesterdays, but the focus of Gaël Méheust – the 11th president to head the joint venture – is very much on what happens tomorrow and beyond

Reaching a 50th birthday as the world’s most successful engine maker is certainly something to be proud of – especially given that CFM International barely made it to its fifth (see History P6). However, Gaël Méheust, the joint venture’s president and chief executive for the past seven years, has his sights set as much on the present and future as the business’s illustrious past.

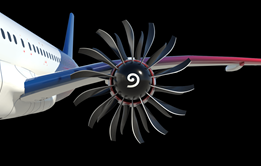

His focus – and that of CFM’s shareholders GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines – includes steering the fast growing but still youthful LEAP engine fleet towards maturity, a target he hopes to reach sooner than some might have expected. Another is exploring the potential of the RISE (Revolutionary Innovation for Sustainable Engines) research and technology project to transform the commercial aviation propulsion market beyond the 2030s.

The fact that the Open Fan study was launched under the auspices of CFM in 2021 as GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines signed an agreement to extend their ground-breaking partnership to at least 2050 was highly significant, believes Méheust. “Our industry committed to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and as the leading engine manufacturer, we want to be there to lead that effort,” he says.

More than three years into the project, he and his colleagues are “extremely happy with progress”, with more than 250 tests conducted, including in the wind tunnel to understand the interaction between the large Open Fan propeller and the wing, as well as evaluations of new generation turbine blades using an adapted F110 fighter jet engine and a GE Aerospace-designed core.

RISE is aimed at developing disruptive technologies that could evolve into an in-service engine a decade or so from now. However, the priority with CFM’s previous transformative product – the LEAP engine launched in 2008 – is resolving any remaining teething problems. Eight years after the LEAP entered service, the fleet has surpassed 60 million engine flight hours and the point at which it can be classed as a mature programme.

Such remedial measures include the recent addition of a reverse bleed system (RBS) on the Airbus A320neo family’s LEAP-1A. The RBS, which mitigates carbon build-up on fuel nozzles, will also be applied to the Boeing 737 MAX’s LEAP-1B and is available as an on-wing retrofit on existing aircraft. Méheust calls it an example of CFM’s commitment to “product improvements designed to meet customer expectations for our engines”.

However, further design tweaks to squeeze additional efficiencies are, for the present, not on the agenda. “Right now, we want to do nothing to LEAP but continue to accumulate cycles to achieve the maturity it is rapidly attaining,” says Méheust. Minor issues aside, the LEAP was “right the first time”, he says, with some customers reporting performance improvements of more than the promised 15% over previous generation engines.

“The risk of making changes today to try to obtain a little more performance risks moving further back on the maturity curve,” insists Méheust, who helped introduce the LEAP to the market in his previous role as executive vice-president of sales and marketing for Safran Aircraft Engines. “That is not to say we will never infuse new technology [into the LEAP], but now is not the time. What took the CFM56 decades, LEAP has done in a few years.”

For all his attention on the future, Méheust is happy to reflect on the remarkable legacy of the business he now runs. Acknowledging the contribution of all his current and former CFM colleagues, including founding fathers René Ravaud and Gerhard Neumann and those who preceded him as president, he says: “Their biggest achievement was bringing it from nothing to the number one engine manufacturer.”

He adds: “Fifty years ago, very few believed this joint venture could be selected to power any aircraft. Five years later, the programme was two weeks from being terminated. Since then, we have produced more than 42,500 engines. Every two seconds a CFM-powered aircraft takes off, and CFM-powered aircraft carry seven-and-a-half million passengers daily. They represent around 75% of all single-aisle aircraft flying today.”

The joint venture itself was the most unlikely pairing – a state-owned engine maker that had previously only dabbled in the commercial market and a US conglomerate. “You had two completely different cultures,” he says. “And remember that in 1974 there were no cell phones, no video calls, no digital mock-ups. You had two sets of engineers, on two continents, speaking two languages. Even communicating was difficult.”

Ravaud and Neumann, however, never doubted. “Our founding fathers firmly believed that this partnership would create value,” says Méheust. The formula they laid down in their early meetings is one that has held true for 50 years – each company manages its own supply chain and owns and is responsible for its own technology and sub-systems. Final assembly is split 50/50, as are revenues, and all major decisions are taken collectively.

“They made smart decisions and the right ones,” says Méheust. “Their philosophy was always that one plus one is greater than two. There are two different brains to assess a situation and make a decision. It sounds counterintuitive, but we are often stronger when the two parents have different opinions. There has to be a compromise, and it’s usually a wise one. You might say that our strength comes from our disagreements.”

In practice, this obsession with finding common ground needs “strong processes, milestones and gates to align strategy”, says Méheust. “We talk a lot, and we foster the idea of always putting yourself in the other person’s shoes. If not, you can get stuck in your own position. Over the years, we have all learned to listen to and appreciate the other view, because it might be the winning idea at the end of the day.”

The RISE project – which is looking to commercialise a technology never previously deployed in a certificated engine – is an example, according to Méheust, of where the combination of each partner’s proprietary research and development studies and transatlantic cooperation between engineering teams is reaping rewards. “RISE gives us a real opportunity to converge and collaborate on R&D,” he says.

Méheust, who joined the Snecma group in 1984 after graduating with a master’s degree in international business, is the 11th CFM president (these days also called chief executive) since Jean Sollier in 1974. By tradition, the position is held by an employee from the French company who is aided by an executive vice-president from each parent, as well as vice-presidents of contracts and finance, also seconded from GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines.

Méheust’s role is to be the company’s “face” in its relationships with customers, government agencies, industry bodies, and the media. He also has responsibility for the worldwide brand awareness and reputation of CFM and serves as the interface between top management at the shareholders – the CFM central team is tiny with almost every function caried out by one of the two partners.

The agreement signed between GE Aerospace and Safran to extend CFM International until at least 2050 will see the joint venture celebrate its 75th birthday in 2049. We do not know how far down the road to its net-zero goals the industry will be at that point, but it is certain CFM technology will be helping to propel it on its way.

Perhaps too by then, a new generation of engineers in the US and France – some not yet born – will be working on the next big thing in commercial aircraft propulsion, an innovation for the second half of the century that could see the two parents renew their marriage vows again and again. Who indeed would bet against a CFM centenary in 2074?

CFM International at 50

It was a marriage many said could not last and some tried to stop happening. But like many unlikely unions, the 1974 coming together of General Electric and Snecma (today, GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines) has endured and prospered. Fifty years on, their creation, CFM International, is the most ...

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

CFM International at 50: Chief executive Gaël Méheust on what comes next

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10