Half a century ago, a prototype aircraft lifted off for the first time, one that 50 years later has become an icon of military aviation and among the most-produced helicopters of all time.

In 1974, that developmental rotorcraft was known as the YUH-60A Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS). Today, the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk is one of the most-recognisable aircraft in the world, with more than 5,000 examples delivered by the US rotorcraft manufacturer.

Only a handful of military helicopters boast greater proliferation, with the shortlist including the Soviet-designed Mil Mi-8/17 and Bell’s UH-1 line.

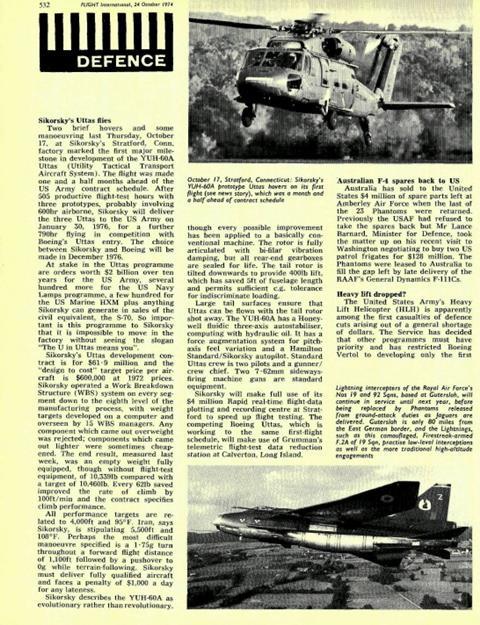

The Black Hawk’s bountiful progeny began with the type’s first sortie on 17 October 1974 from Sikorsky’s flagship campus in Stratford, Connecticut.

At the time, Flight International described the milestone as “two brief hovers and some manoeuvring”, noting the first flight was achieved six weeks ahead of the UTTAS programme schedule.

So long ago was it, that Flight’s coverage of the event lauds weight tolerances that were “developed on a computer” and notes aerodynamic performance requirements submitted by Iran, then a US ally and customer.

The UTTAS development effort was launched by the US Army in 1972 with the goal of replacing its UH-1s with a “simple, robust and reliable utility helicopter”, according to the army. A solicitation to industry was issued that year with Sikorsky, Bell and Boeing Vertol responding.

The YUH-60A triumphed in a competitive fly-off against the Boeing Vertol 179, designated the YUH-61A by the army, with the official selection coming in 1976. Deliveries of the first production model UH-60As began in 1978, with the type entering frontline service the following year.

With the Black Hawk, the army continued its trend of naming rotorcraft after indigenous tribes of North America. The UH-60 was preceded by the UH-1 Iroquois, and the Bell H-13 Sioux. “Black Hawk” was the name of a leader from the Sauk tribe who fought against the USA in the War of 1812.

According to the US Army, the naming tradition began in 1947 when General Hamilton Howze was assigned to develop doctrine for how new aviation assets could support ground combat troops.

Howze apparently was not a fan of earlier names, including the Sikorsky R-4 Hoverfly and Westland-Sikorsky R-5 Dragonfly.

According to the National Museum of the US Army, Howze associated the speed and agility of early helicopters with the horse-borne warriors of North America’s Great Plains, who fought a bloody, decades-long struggle in the 19th Century against forced displacement, often by the US Army, amid America’s westward expansion.

“Howze said since the choppers were fast and agile, they would attack enemy flanks and fade away, similar to the way the tribes on the Great Plains fought,” the army said in 2020.

The first aircraft to receive an indigenous name was the H-13 Sioux, whose namesake tribe famously defeated the US Army’s George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn. That same tribe later contributed their name to a second army rotorcraft, the Airbus Helicopters UH-72 Lakota, which is how members of that tribal nation refer to themselves.

Although the tradition has attracted scrutiny in recent years, the army says the names are meant to invoke the “spirit, confidence, agility, endurance and warrior ethos” of North America’s native peoples.

Endurance is certainly an apt description for the Black Hawk. Approaching its 50th year of active service, the multi-role helicopter remains the backbone of the US Army fleet, with 2,135 UH-60s in service, according to Sikorsky.

The type achieved household-name status after the 1999 publication of Black Hawk Down and the associated film, which chronicled a deadly 1993 special operations raid in Mogadishu, Somalia that saw two UH-60s lost to enemy fire and 18 US Army personnel killed, including multiple aviators.

Nearly 20 years later, in 2011, Black Hawks heavily modified for a stealthier radar profile and lower acoustic signature ferried US Navy commandos deep into Pakistan for the raid that killed Osama bin Laden.

In conventional operations the type performs a diverse range of missions, including troop transport, logistics resupply, medical evacuation and special operations support, logging some 5 million combat flight hours in the process.

“It’s the workhorse of the US Army,” says Jay Macklin, a retired UH-60 aviator who now oversees business development for Sikorsky’s US Army and US Air Force portfolio.

Macklin commanded an army aviation task force in Iraq during the so-called “surge” of 2007-2009 that saw some of that war’s heaviest fighting. During that deployment, he says the Black Hawk “really shined” when delivering combat troops into battlefield landing zones (LZs) – what the army calls “air assault”.

Macklin cites the UH-60’s compact footprint, speed and manoeuvrability: “We were able to fly in very close formations and land at night in pretty tight landing zones, basically where the enemy wasn’t expecting us”.

However, it is the Black Hawk’s rugged ability to absorb enemy fire and keep flying that truly sticks with him.

“The aircraft can sustain hits, it can continue to fly, you can land in an LZ pretty hard at night,” Macklin says. “It’s just an incredibly durable aircraft.”

That survivability was critical to the missions that stick with Macklin the most: evacuating wounded troops from hostile territory.

“Infantrymen would tell me, ‘When I heard the rotor blades of the Black Hawk coming, I knew everything was going to be alright’”, he says.

While the Black Hawk has proven extremely rugged throughout its first 50 years, the Pentagon is now considering how to maintain that record in the face of increasingly common – and effective – guided munitions popping up in conflicts around the world.

This year, the US Army committed to buying more UH-60s and flying the rotorcraft for another three decades. But the service is also moving to procure the Black Hawk’s successor – Bell’s V-280 Valor tiltrotor, which boasts significantly improved range and speed.

That has officials in Washington DC and at Sikorsky exploring new roles and new capabilities for the venerable UH-60.

“The Black Hawk of tomorrow must be better than the Black Hawk of today,” says Hamid Salim, Sikorsky’s vice-president of army and air force programmes, who oversees the entire H-60 family of aircraft.

In the near term, that means more powerful GE Aerospace T901 Improved Turbine Engines to replace the two T700 powerplants currently onboard. These will deliver increased range, payload and performance for both the UH-60 and Boeing AH-64E Apache attack helicopter.

Sikorsky plans to begin testing the new engine on a Black Hawk later this year.

The T901 was primarily developed for the now-defunct Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA). The army cancelled development of that next-generation armed scout in February, citing concern over the survivability of a manned helicopter meant to fly deep into enemy territory.

However, FARA’s demise may open an opportunity for the Black Hawk.

Sikorsky is experimenting with a number of new technologies that could help the 20th Century troop carrier evolve into a powerful intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance asset in the 21st Century. “We’re going to pick up some of the FARA missions,” Salim says.

Under the broad umbrella of “launched effects”, the army is seeking to deploy numerous small drones that could be used individually or in swarms to provide battlefield reconnaissance and communications retransmission, or to deliver lethal strikes.

Salim argues the Black Hawk, with its massive existing fleet, has huge potential as a delivery vehicle for those assets.

“Picture a future battlefield with thousands of small drones that are flying for reconnaissance or to deliver payloads,” Salim says. “That helicopter can actually carry those effects, launch those drones and put them near where they need to be and control them in a way that is very effective.”

Sikorsky has already proven the ability to launch such small uncrewed aerial vehicles from multiple H-60 variants, including the standard UH-60 and MH-60 special operations type.

The company says it also has a solution to the problem that truly ended FARA: putting crew in unacceptable danger.

While currently deployed Black Hawks fly with at least two pilots and a crew chief, Sikorsky has developed technology that enables the UH-60 to fly completely autonomously.

Called the Optionally Piloted Vehicle (OPV), the experimental platform is a modified Sikorsky S-70, the civil version of the Black Hawk. It was developed in partnership with the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and has proven capable of autonomous take-off, landing and obstacle avoidance without the need for pilot input.

Senior Pentagon officials, including army secretary Christine Wormuth and former Air Mobility Command boss General Michael Minihan, have tested the technology, controlling an OPV Black Hawk with nothing more than a touch-screen tablet.

As the “optional” in OPV implies, the technology still allows for conventional flying with a pilot at the controls. The ability to switch a rugged, multi-mission platform like the Black Hawk between crewed and uncrewed flight is a tantalising prospect for Macklin, the retired army colonel.

“Commanders always liked to have a lot of flexibility,” the former battlefield leader says. “Having those options, I think, will really make a difference.”

He recalls an incident in Iraq where an American base taking hostile fire requested an urgent resupply of ammunition from the task force’s UH-60s.

“I had to put two crews in harm’s way on an extremely high-risk mission,” Macklin recounts. “If I had this technology, I literally would have programmed one aircraft to pick up, fly, land and come back.”

In a less extreme case, Sikorsky’s autonomy technology could be used to reduce pilot workload and increase safety. A more-limited capability is already incorporated in the company’s CH-53K King Stallion heavy-lift type, which allows the rotorcraft to assist pilots with landing in low-visibility conditions, such as at night or amid rotor-wash brownouts.

While the USA develops plans for the Black Hawk’s future, the current UH-60M model remains popular globally. Sikorsky has racked up numerous overseas orders in the past two years, including from Australia, Austria, Croatia, Greece, Jordan and others.

Production and deliveries of other H-60 derivatives, including the MH-60R Seahawk and HH-60W Jolly Green II combat search and rescue platforms, are also ongoing.

“Evolutionary rather than revolutionary” is how Flight International quoted Sikorsky’s description of the early YUH-60A prototype. That story from 1974 notes the first Black Hawks were conventional helicopters, but with “every possible improvement” having been applied to the new design.

Fifty years later, the Black Hawk appears poised for another major evolution.

If the type continues flying until its 100th anniversary, 2024’s exultations of autonomy and artificial intelligence may seem as quaint as praising the original UTTAS prototype for being “developed on a computer”.