Sophisticated health monitoring technology together with a global network of specialist MRO providers help keep CFM engines performing profitably for their operators over a long lifetime

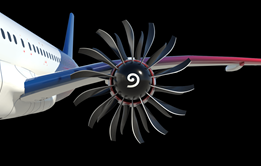

Forty-two years after the first CFM56-powered passenger flight, 24,000 examples of the iconic engine are still in operation around the world, and 45% of these have yet to make their first shop visit. Add to that a rapidly expanding and maturing LEAP fleet that has surpassed 60 million flight hours and you get an idea of the scale of CFM International’s responsibility to support its customers – today and for decades to come.

Much is written about the GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines joint venture’s success in developing, winning a market for, and delivering CFM56 and LEAP engines. But just as important is the effort the partners make to ensure its in-service engines keep performing efficiently, reliably, safely, and profitably over such a long time – for both engine families a combined 1.3 billion flight hours and counting.

Since its first engines began to appear in the aftermarket, CFM has stuck to the principle of an open maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) ecosystem, allowing airlines to opt for a facility run by GE Aerospace, Safran Aircraft Engines, or an approved third-party. It believes this improves the customer experience by boosting choice and service quality through competition.

The global CFM network today comprises 35 sites, most of which specialise in the CFM56 engine. Five operations under so-called CFM-branded service agreements or CBSAs are equipped to maintain the LEAP engine and are run by some of the MRO sector’s biggest names – Air France Industries-KLM Engineering & Maintenance, Delta TechOps, Lufthansa Technik, ST Engineering and Standard Aero. Another 11 licensed shops make up the global coverage.

As the LEAP fleet grows the stakeholders are committed to further investment, with GE Aerospace in July announcing a $1 billion boost for its MRO facilities over five years. Although the funding will also benefit the manufacturer’s other engine types, the largest chunk of the investment will go into supporting LEAP customers, including at its XEOS facility in Poland – a joint venture with Lufthansa Technik – as well as shops in Brazil and Malaysia.

Safran Aircraft Engines is also growing its LEAP capabilities, announcing in July that it is to spend $80 million building a second MRO shop in Querétaro, Mexico, which is scheduled to begin operations by 2026. The company also in June opened a LEAP facility in Brussels and will follow that with an overhaul shop in Hyderabad, India. That site will have an annual capacity of 300 visits and be operational next year.

Two recent service bulletin retrofit programmes for LEAP engines are also being rolled out. An innovative reverse bleed system designed to reduce on-wing fuel nozzle replacements caused by carbon build-up is now available for the Airbus A320neo’s LEAP-1A engine. Meanwhile, an improved high-pressure turbine blade is on track for introduction by the end of the year.

Since the arrival of the CFM56 engine, GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines have coordinated support networks for their customers, with GE Aersopace leading in the Americas, Asia, and Oceania, and Safran in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. However, with the rapid ramp-up of LEAP engine deliveries, the two CFM partners decided they needed a fully integrated On-Site Support (OSS) network to provide on-wing and quick-turn engine support.

Under the initiative, terms and conditions and regulatory compliances were amalgamated. All the OSS sites, which are staffed by around 200 technicians, have Federal Aviation Administration and European Union Aviation Safety Agency approvals, and can handle most line maintenance activity, such as diagnostics and replacement of certain components. Ten of the facilities are also equipped for quick-turn maintenance events.

In addition, CFM’s front-line when it comes to support is its 250 field support engineers (FSEs), who are positioned with customers around the world. A vanguard of these FSEs began training on both the LEAP-1A and LEAP-1B engine ahead of their entry into service, participating in the flight test programme for both the Airbus A320neo and 737 MAX and helping ensure what CFM describes as its smoothest ever service introduction.

CFM says that one of the barometers of the effectiveness of its support operation is the number of AOG or aircraft on ground incidents related to an engine. The LEAP fleet’s ratio is just 1.2%, a significant improvement over the CFM56, but, as importantly, bettering the competition by some margin.

While engine health monitoring has been offered on the CFM56 fleet for more than 10 years, the arrival of its successor has seen an intensification of predictive maintenance capabilities. Multiple sensors on every LEAP engine record a host of data from temperature and pressures to vibrations. Then, using sophisticated machine learning, diagnostic software signals any aberrations.

According to CFM president Gaël Méheust, the technology has led to 17,600 notifications being sent to operators in the past year, helping to prevent more than 2,500 significant maintenance events. “Engine health monitoring plays a huge part in keeping operating costs under control and customers’ engines flying,” he says.

CFM International at 50

It was a marriage many said could not last and some tried to stop happening. But like many unlikely unions, the 1974 coming together of General Electric and Snecma (today, GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines) has endured and prospered. Fifty years on, their creation, CFM International, is the most ...

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

CFM International at 50: Maintaining a difference

- 8

- 9

- 10