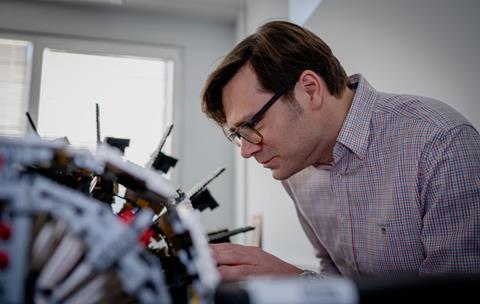

What started as a fun family activity for GE Aerospace engineer Michał Janczak became a passion project that put his engineering skills to the test. Using 19,000 LEGO bricks, he worked to build a replica of the pioneering RISE program’s open fan engine architecture being developed by CFM International.

Michał Janczak was a 10-year-old growing up in Warsaw, Poland, when he received his first LEGO Technic set. Technic components, which include rods, gears, and other specialized parts in addition to the basic LEGO bricks, weren’t available in Poland at the time, but his father bought him a set while on an international business trip. The gift helped Janczak create countless new creations while paving the way for a future design engineering career. “That was when I started to see LEGO bricks as a serious tool to express my creativity,” he recalls. “In my childhood, every day without LEGO play was a wasted day.”

Now an advanced lead engineer at GE Aerospace’s engineering center in Warsaw, Janczak works mainly with rotating metal parts, performing stress analysis. But his passion for the iconic plastic bricks lives on, as evidenced in his latest masterpiece: a scaled 19,000-piece LEGO brick replica of the pioneering design being developed through the Revolutionary Innovation for Sustainable Engines (RISE) program by CFM International, a 50-50 joint company between GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines.

Revealed to the public last October at the Night at the Institute of Aviation, a showcase of aerospace technologies in Poland, the replica built with LEGO bricks is a feat of engineering in itself. Nearly five feet long and weighing around 40 pounds, it features dozens of moving parts and true-to-life details, including a spinning open fan with variable-pitch fan blades. By bringing an accessible, somewhat playful perspective to some serious advanced technology, the LEGO brick model invites people of all ages to learn about the RISE program, which aims to transform air travel by reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions by more than 20% compared with today’s most efficient engines.

Janczak came up with the idea for the model last spring, as the end of the school year was approaching for his sons Franciszek, 15, and Antoni, 12. “My initial intent was to create an activity for the summer holidays for them, something we could build together,” he says. But creating the design, which he based entirely on information publicly available on the internet, was more complex than he’d anticipated.

Working on his home computer and using BrickLink Studio, a free 3D design application developed by the LEGO brand, he spent long nights and weekends on the project. Still, it took until August to complete the design and edit its more than 200 pages of documentation. His sons helped him construct preliminary stages, but they were back in school by the time the real building phase began.

At that point, thankfully, Janczak’s colleagues stepped in to help. To get more people involved and to speed up construction, the company held building workshops, supervised by Janczak, and invited employees to participate.

“These people were not just passive assemblers; they were collaborators, providing ideas about how we could make things better,” Janczak says, expressing gratitude to the 18 GE Aerospace team members who pitched in to build the model.

The project, which reached the final assembly stage in early October, engaged Janczak’s engineering and problem-solving abilities and allowed him to practice time management, team building, and documentation skills. His organizational skills, too, were put to the test. “You can imagine that if you have 19,000 small bricks in something like 200 boxes, it’s really easy to lose something,” he says. “And there were no spare parts.”

The model contains only a few non-LEGO components, such as metal ball bearings and computer-operated electronics that power its moving parts. In addition to its open fan architecture, it features a functioning gearbox and working mechanisms that control pitch change and more. A modular design allowed segments of the engine to be built in parallel and to be perfected individually before they were brought together for final assembly.

“In that way, it mimics the architecture of the real engine,” Janczak says. “Obviously, the real engine is much, much more complex, and one person could never design it. But some of the issues presented in building the LEGO model are similar to those seen in real life — you have to consider the rigidity of the structure, for example, and the clearance between rotor and stator.”

Now the LEGO brick model of the open fan engine is proudly displayed at the Warsaw office and will be used for engine layout demonstrations and training sessions. And Janczak has much more free time to practice his other artistic passion: vocal music performance. In addition to earning a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the Warsaw Institute of Technology, he holds a master’s in music from the Warsaw Academy of Music and enjoys performing sacred music in churches and other Warsaw venues.

Still, he keeps thinking about the LEGO build and plans to make a few minor adjustments. “I have a very strong emotional connection to this model,” he says. “I have been interested in global climate change for many years, and the RISE program gives me the feeling that our work is heading in the right direction, that we are looking toward the future for our children.”

See the build come together.